|

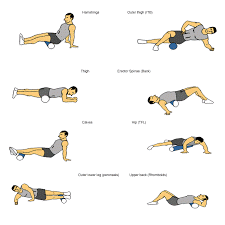

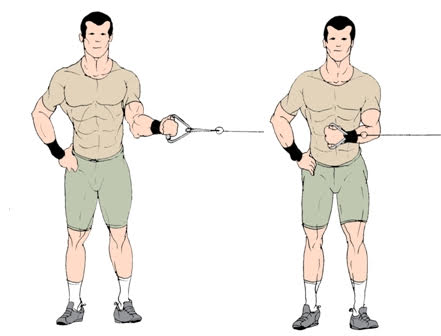

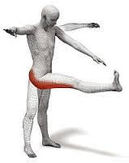

James DeAndressi B.S, NASM-CPT has been interning at SportPerformanceU this summer and will be today’s guest blogger. James earned his bachelor’s degree in exercise science from Southern Connecticut State University and is planning on attending school this fall to become a physical therapist assistant. Below you will find his piece on why including a proper warm is so important. It is clear based on research, observation, and comparison that a good warm up before a workout can increase the overall quality of how you spend your time in the gym. The question is however, what makes up a good warm up and why is the warm up part of the workout important? All trainers may have different opinions and different ways of training but for the most part, it is fair to say that most qualified trainers in any setting should agree with the warm up being a key part to an individual’s daily routine. At SPU we will typically start a client with soft tissue work as well as some specific dynamic warm up exercises. Soft tissue work for a client will be mainly foam rolling or simple active massage unless the trainer is certified and/or licensed as a professional health care provider. They need to be legally bound to doing some type of manual soft tissue work on a client. Foam rolling is safe, effective, and backed by research to roll out fascia to fix cross linked muscle fibers. This will in turn make the muscles fire and perform the best it can for that specific person at that specific time. Foam Rolling Techniques A good warm up needs to consist of anything we as trainers believe will have a positive impact on our client during the workout. Mobility, or in other words, the ability to move freely through a given range of motion is one component to a good warm up. Exercises to increase range of motion include ankle dorsiflexion at a wall or shoulder wall slides. Corrective exercises are another key component. These exercises will be put on a client’s program depending on the results of some type of movement analysis. Corrective exercise is a broad topic but in the simplest of terms, they are specific exercises that will be targeting some type of human movement deficiency. Examples of some corrective exercises would be Unilateral or Bilateral Internal/External Rotation of the shoulder joint or hip joint and bird dogs to increase core stability as well as to strengthen a specific deep muscle connected to the spine which can cause pain. Trainers should take note of any types of movement deficiencies during every training session in order to progress or add/subtract corrective exercises. In other words, analyzing movement should not be an afterthought but should be constantly on a trainer's mind during sessions. To learn more about SPU’s specific biomechanical analysis, read our blog which gives some detail on this topic. Dynamic exercises are another way we can prepare a client’s body for the upcoming workout. At SPU this is the final part of the warm up before going into our power, strength, speed, and conditioning blocks. According to Eric Cressey, in his book Maximum Strength “we are focusing on raising body temperature which in turn will raise muscles temperature. Lubricating muscles and joints as well as increasing mobility in key joints while enhancing stability in others in order to perform strength movements more efficiently” is also part of the equation. Some examples of dynamic exercises would be leg raises or a lateral shuffle. Trainers who understand the importance of a well-balanced exercise program will have a warm up section that is not overlooked, rushed, or inefficient. For a client’s own personal well being, I would recommend changing trainers if they did not properly warm up a client before a workout. Fitness professionals should all look at the warm up as a line of defense, if you will, for decreasing injury. As fitness professional including a solid warm up is a necessity.

0 Comments

We get a lot of parents and athletes asking us for exercises that are "specific" to their sport. Hockey players want hockey specific training, football players want programs that relate to their position, etc. And rightfully so - most athletes who train are doing so with performance in mind. They want their work in the weight room to translate to the fields of play. The question is, what constitutes a sport-specific exercise and how much does an athlete need to train in that way?

It is true, some exercises are similar to movements we see in sports, and therefore translate quite well. Take, for instance, a quarterback doing rotational medicine ball work. Or, take a boxer doing a landmine single arm press. These movements are both visually and functionally very similar to way an athlete would move while playing the sport. What we must remember is that a training program that consists only of these "specific" movements is not a well rounded program and can lead to decreased performance and injury. Exercise selection should first take into account each athlete's biomechanical integrity. If an athlete is restricted in a certain movement, we can't load it no matter how specific it is to their sport. We first must fix the pattern before moving onto the loaded exercise version. Take a squat - this movement I would consider "specific" to offensive lineman; they move and push in bilateral patterns, and their firing out of a stance can be similar to a squat. So, for offensive lineman, yes, we would like to program squats. However, if an athlete fails the squat portion of our analysis and doesn't yet possess the mobility and stability to do the movement properly, we can't just throw it into the program because it is "specific." Exercise selection needs to be specific to the athlete before it is specific to the sport. If an athlete has the mobility and stability to do the required movements then we can begin to specify. What that means is when we choose exercises for each major movement (push, pull, knee dominant, hip dominant, etc), we choose exercises that relate to their sport. However, we won't leave a major movement category. So, when looking at what knee dominant movements we want to accentuate, we might choose a rear-foot elevated split squat for a wide receiver, and a front squat for a lineman. The end point here is that doing exercises that are specific to a sport is important for athletes who are ready and capable, but don't take that for granted. Many athletes need to work on movement patterns, mobility, and stability before they can progress to some of the "specific" exercises. How many athletes are required to perform a movement analysis before starting a performance training program? My guess is that most athletes are not. Let me ask another question. What happens when an athlete is asked to perform a back squat or any movement for that matter, which is dysfunctional in nature due to their physical limitations? Strength is added to that dysfunctional movement pattern, it is not added to the true functional movement pattern. I’m going to continue to use the squat as my main example because it is probably the most common exercise used in most high schools. The squat is an amazing exercise for building strength, but when it is performed before athletes are ready for the movement bad things can happen. Below are some pictures that illustrate what an improper squat pattern looks like. These faulty squat patterns could be due to an array of reasons, some of which include short/weak hip flexors, imbalance of core musculature, excessive pelvic tilt, limitations with ankle mobility, weak glutes, etc. A complete movement analysis must be done to understand the complexity of these dysfunctional squat patterns. All of the above pictures demonstrate a faulty squat pattern that needs some cleaning up. Below is a picture of a squat pattern that is ready to be loaded with external resistance. If you are not performing a movement analysis of some sorts you are doing a disservice to your athletes. It is literally the foundation of any worthwhile performance training program.

The off-season is a time to recover from any injuries that were sustained during the regular season, take care of any asymmetries that were developed from the specific sport played and increase strength, power and speed so that you are ready to dominate during the regular season! The off-season is usually broken down into three sub categories, which include the early, general and late off-season training program. The off-season ranges from sport to sport so when putting together a performance training program the actual length must be considered to program accordingly.

The early off-season is in most cases the first two weeks where there can be complete rest or light physical activity. This is the time to recover both physically and mentally from the regular season. There should be nothing strenuous done during this period. The general off season is the time to focus on cleaning up any asymmetries that might have been acquired during the regular season along with any loss of proper biomechanical efficiency. Once those situations are addressed it is time to begin increasing strength, power and speed components. This should comprise the majority of your off-season. The late off-season is when we should be peaking and focusing on any additional conditioning that is required of the specific sport. This varies from sport to sport and athlete to athlete. For sports that are more aerobically based such as field hockey, aerobic conditioning will be increased earlier in the late off-season then other more anaerobically focused sports. Some athletes also take different amount of time to gain the aerobic level of conditioning that is needed for their sport. The off-season (which encompasses the first day after the regular season ends until the first day it begins) is the time to get stronger, faster and more powerful. You should not start your off-season training a few weeks or even months before the beginning of the regular season. If being your best on the field is important to you, then taking your off-season performance training seriously is required. This is the time to put in the work so you can reap the benefits during the season. The biomechanical analysis is performed before even thinking about what sport performance program will be written for an athlete. It is literally the first step in figuring out what an athlete needs in their program. It is not a measurement of how strong or powerful they are. The analysis takes into consideration the mobility, stability and neuromuscular patterning of the athlete. We are looking at how well they perform basic movement patterns. The joint by joint approach which is taken by many of the top professionals in the field approaches the body as alternating mobile and stable joints. An example of this would be how the ankle is a mobile joint and the next joint up the kinetic chain; the knee is a stable joint. There has to be a balance of mobility and stability while performing movement to be efficient.

At SportPerformanceU we perform ten different tests during our biomechanical analysis. Each test encompasses the ability to be both stable and mobile as is the case with any athletic or functional movement that is being performed. The overhead deep squat is one of our ten tests that look at multiple things during one movement. We are examining the ability of the ankles, hips and thoracic spine to be mobile while the knees, lumbar spine, and shoulders are stable. This test also looks at the neuromuscular patterning of the body. This is the motor learning process, where the muscles learn to “fire” properly and efficiently. An example of this would be examining an athlete that has the ability to perform an overhead deep squat in the supine position, but when standing is not able to accomplish the same task. The stability and neuromuscular firing patterns needs to be cleaned up. This is just one of the ten tests we do to get a full picture of what each athlete needs. Everyone is an individual and desires a training program that is specific to them. It is so important to perform this biomechanical analysis to have a starting point for each athlete. If an analysis is not done it becomes a guessing game. And I do not want the training programs I write for my athletes to involve any guess work. |

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed